[Part One of a two-part series]

Mama used to say, every time she was sick, “I’ve never been so sick in all of my life.” EVERY time.

I’d say, “Mama, you always say that. If you got sicker every time than you were the last time, you’d be dead by now.”

I offer that to say that when that the call came, the one every child dreads, I was very sick. I had been sicker before but it was only the third time in my life that I had gone to bed for almost a week. I woke up that morning, feeling so bad that I went back to bed, determined to sleep until I had healed from a viral infection I had picked up on a plane.

Around 2 p.m., I awoke and wandered through the house to find Tink. Just as I passed through the foyer, I heard him answer the phone. I saw him sit up straight and ask urgently, “Has my father died?” Alarmed, I stopped and looked at him. In a second or two, he nodded in my direction. I sat down on the step that leads into our sunken living room and, with heart already aching, waited until he ended the call.

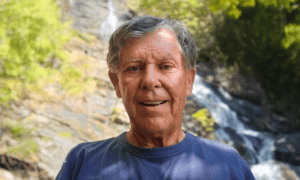

Grant Tinker, a man who loved me and who I loved, was gone. We had spoken to him three times in the past few days and he had sounded fine. But during the night, the mighty heart of a mighty man had ceased to beat. I was terribly sad for my husband because it’s hard to lose your father but I was just as sad for me. I adored him and he delighted in our conversations.

It’s hard to explain how two people so different could connect like we did. He was Ivy League educated, descended from the Mayflower, and one of the most legendary men in television history. I am from poor people of the Appalachians, descended from poor Scotch-Irish who escaped poverty in Northern Ireland and my greatest career boost came from working among the grease monkeys of stock car racing.

Every time we left Grant Tinker’s house, Tink looked at me and said, often with tears in his eyes, “I am so proud of how much my father loves you. It is such fun to listen to you two talk.”

The last thing I ever heard him say, was, “Love you guys.” I shook my head in amazement. Usually, he responded when I said, “We love you, Grant Tinker,” with “you guys, too” or “love you.” But this time it wasn’t a response. It was a statement.

Tink and his brother, Mark, decided that since their father had been Chairman/CEO of NBC that they should allow NBC to break the story of the death. I wrote the press release/obituary and it was sent off. The next morning, Matt Lauer of the Today Show delivered the news, quoting the mantra Grant used in taking NBC from third place into the top spot, “First be best then be first.”

“Poor Grant Tinker,” I said as we watched the NBC Evening News which announced his death after another’s. “He had the misfortune of dying on the same day as the inventor of the Big Mac so he had to play second fiddle.”

Tink laughed. “He would have thought that was funny.”

Here’s what I didn’t think was funny. A man who thought I was smart and funny, who encouraged me and loved my stories was gone. Grant Tinker did something that my own daddy had never done: He read all my books and many of my newspaper columns. Daddy died before my first book was published.

“All the people who love me keep dying and those who hate me go on living,” I said glumly.

Tink chuckled and hugged me.

I had never been as sick in all of my life.

[Ronda Rich is the best-selling author of the “What Southern Women Know” trilogy. Visit www.rondarich.com to sign up for her free weekly newsletter.]

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.