In Romania, the regime starved its people. In America, policy choices do the same.

Snowflakes spun in the streetlights that night, cold and glittering, as we hurried down the dark boulevard. I was eight going on nine, and my mother, then a young mathematics professor, had been invited to a holiday party at a colleague’s apartment, another grey concrete block in Bucharest. On the outside, it had the same bleak façade we all lived behind. But the moment the door opened, I stepped into another world entirely.

Heat hit my frozen face first, a punch of warmth so intense it almost hurt. Their apartment glowed. Light. Music. Laughter. Cigarette smoke curling toward the ceiling like forbidden incense. And on the table: abundance. Deviled eggs, cheeses, salamis, fresh bread, sarmale, mititei, cozonac, other desserts. To an American child, it would have been an ordinary holiday spread. To us, it was a small miracle. Because outside that door, Romania was starving.

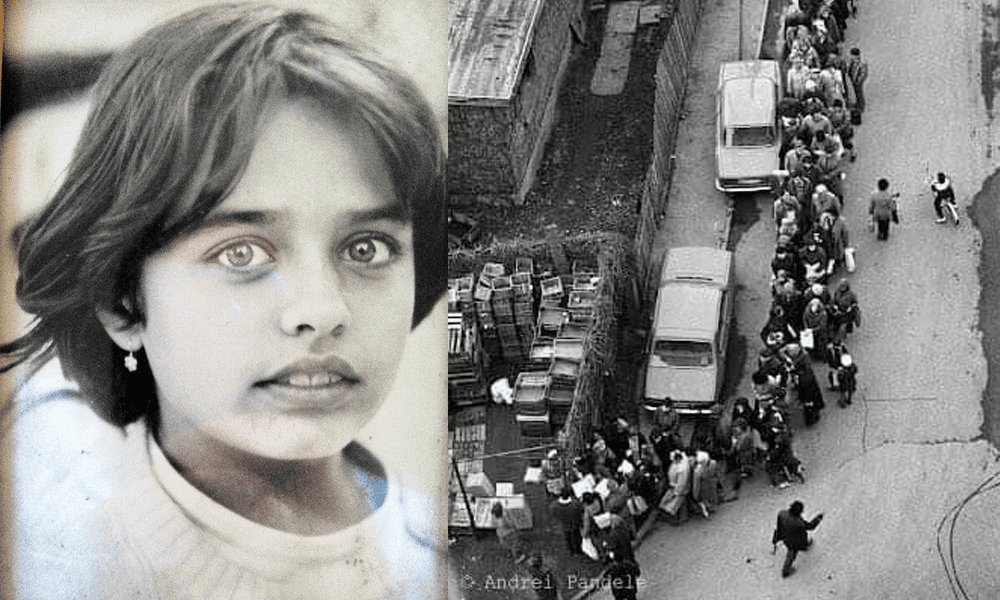

Middle-class professionals like my parents were living with rationed oil, sugar, electricity, heat, and hope. Food lines wrapped around blocks. All of it the result of Ceausescu’s austerity measures, disguised as a “scientific eating program” supposedly for our own good: the lie that we were overeating while the nation wasted away. Hot water came once a week, maybe. In the dead of winter, when the Crivăț winds tore through the capital with Siberian ferocity, we slept in hats, coats, and layers of sweaters beneath stacks of blankets, our breath visible in the dark. Many kept their winter coats on indoors because apartments were too cold to remove them.

In those years, food and other necessities were as political as speech. The well-connected had enough. The rest of us had little. And those suspected of disloyalty, families like mine, often had even less. We were under surveillance. My grandfather was suspected of “anti-democratic activity,” my mother interrogated by the Securitatea while pregnant. Our lives were curated by fear and scarcity.

So yes, we children were thrilled to go to this party. Thrilled for the warmth, the feast, the brief reprieve from deprivation. And thrilled, almost unbearably so, for the VCR in the living room playing Bugs Bunny cartoons smuggled from abroad. Bugs Bunny, the trickster who outsmarted every puffed-up authority figure, a furry symbol of the resistance spirit we carried silently inside us.

My mother warned us to eat slowly. Our stomachs, she said, might not handle so much richness. But I was a hungry child facing deviled eggs, lovely cheeses, and fresh bread. Moderation was a fantasy.

When it was time to leave, she bundled us tight again, scarves, hats, gloves, layers, preparing us to step from a glowing oasis back into a frozen, glum city. And somewhere along that long walk home, the inevitable happened. All the richness, the cheese, the salami, the eggs, the pastries, rose up in rebellion. I bent over and vomited into the snow.

The shame was instant and overwhelming. Hot tears on a frozen face. My mother’s gentle hand on my back, her quiet, urgent worry. I felt I had failed. Failed her. Failed myself. Failed to hide our deprivation. Failed to rein in my voraciousness. Failed to be worthy of that brief taste of abundance.

For years, that shame sat inside me like an unspoken bruise.

And now, decades later, when I volunteer at food pantries here in Georgia, in one of the wealthiest countries on Earth, that memory rises every time I look into the eyes of someone who never imagined they would need help. Because I see the same shame.

I see it in the young woman who just learned she was pregnant only to be laid off, now seeking food assistance for the first time in her life. In seniors who know skipping fresh vegetables will worsen their health, but inflation leaves them no choice. I see it in caregivers and veterans, in families juggling electricity bills against groceries, medications against rent. In parents whose children are shamed for overdue school lunch accounts. And the lines, the lines. They remind me of the breadlines of my childhood, except now they stretch across American parking lots.

Meanwhile, there always seems to be money for spectacle and force. Masked agents snatching immigrants from sidewalks. Propaganda commercials claiming “criminals” are being removed while we watch mothers pulled from their screaming children and fathers detained leaving their immigration appointments. There’s money for private jets, luxury travel to Formula One, high-gloss political theater. But ask whether we can afford to ensure families do not go hungry, or seniors do not freeze, or working people do not drown in medical debt, and suddenly, we are “out of resources.”

The contrast is painfully familiar. Ceausescu had his gold toilet. Plenty of people here have their equivalents.

And yet, I also see what I saw in Romania during the worst years: people helping each other survive. Neighbors sharing food. Volunteers showing up even when their own cupboards run thin. Communities defending their immigrant neighbors with dignity and courage. People refusing to let cruelty define us. This spirit, quiet, decent, stubbornly compassionate, is the America I believe in.

This Thanksgiving, as I think of the little girl I once was, the cold biting my cheeks, the shame twisting in my stomach, I also think of every person in our community choosing to help. Every volunteer, every individual donating produce from their garden or pantry, every neighbor standing up against fearmongering and for the dignity of those around them.

Hope is not naïve. Hope is not passive. Hope is an act of resistance.

And I hope it finds you, too. Because in the end, it isn’t abundance that defines a society, it’s how we treat those who have been pushed into the cold.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.