By HAROLD BROWN

The Covid-19 pandemic bears a striking resemblance to the Spanish flu

epidemic that peaked in October 1918. Nowhere is the resemblance more striking than in New York City, where the New York Times kept a running count of cases and deaths in the autumn of 1918.

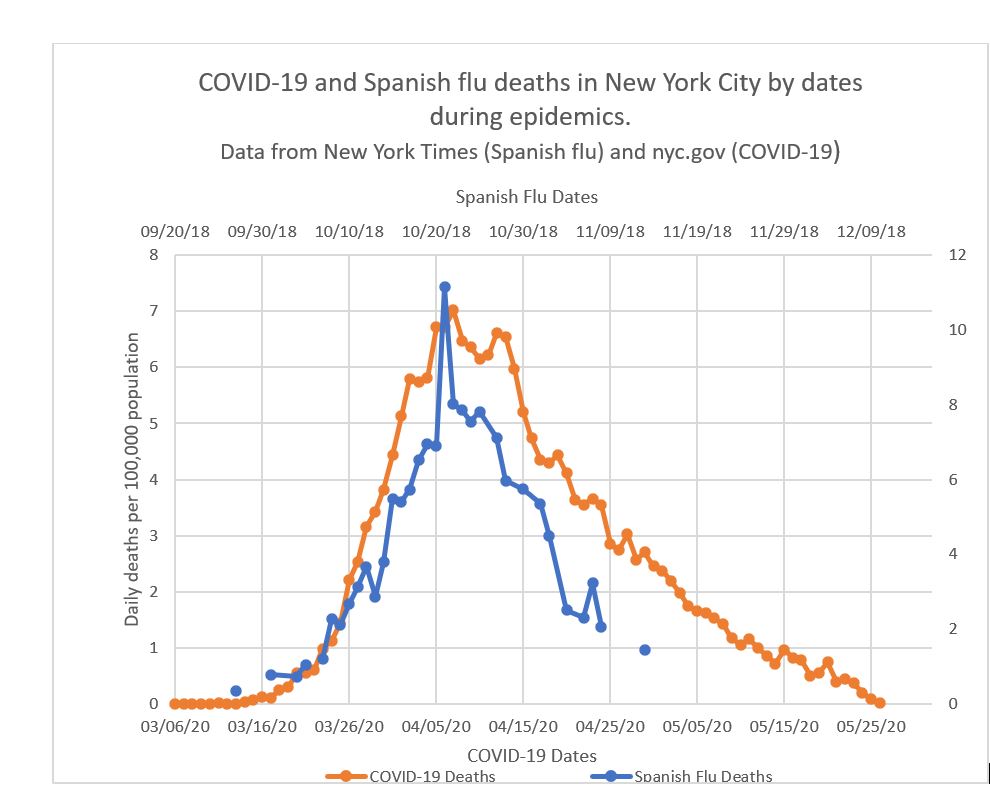

The chart (see below) shows the parallel in death counts. Comparison of the daily number of new cases was similar.

The origin of the Spanish flu and its name are vague. Soldiers returning from Europe could well have brought the 1918 flu to our shores. One history reports “The first officially recorded case … occurred in early March 1918, at a U.S. Army training camp in Kansas.” By early October, there were more than 100,000 cases in Army camps around the nation; The Atlanta Constitution reported 1,893 cases at Camp Gordon outside Atlanta in late September.

“Social distancing” in the 1918 pandemic was similar to today. Early on, (October 3), Philadelphia officials ordered “Schools, churches, theatres, and all places of public assemblage” closed indefinitely. That same day, the Pennsylvania Commissioner of Health closed every saloon and place of “public amusement” in the state.

There was also an emphasis on wearing masks. On October 4, the chief surgeon at Camp Gordon issued an appeal for 100,000 masks and asked the Atlanta chapter of the Red Cross to make them. A San Francisco ordinance compelled everyone to wear a gauze mask, with penalties of $5-$100 and/or 10 days in prison. Several Georgia towns also mandated masks.

New York City health officials regularly issued progress reports, cases and death counts, warnings, closures and advice on containing the plague. Some were premature; many were parallel to today’s conditions in that city and the nation.

Dr. Royal Copeland, New York City’s Health Commissioner, said as early as September 30 that “the Spanish influenza was under control here” and “the worst was over.” On October 9 he surmised that the epidemic was “at least stationary or making but slight progress.” Two days later, he said, “There is still no reason for alarm.”

A week later the number of new cases had risen by 75% and daily deaths had more than doubled. (See chart).

Like today’s rush for a Covid-19 vaccine, a fervent and flawed search occurred then. Dr. Copeland announced on October 1 that a Department of Health bacteriologist “had discovered and would soon prepare for general use a vaccine that would be a preventive against Spanish influenza.”

In mid-October, it was reported that 450 YMCA workers had been given a vaccine, and “the results have been remarkably good.” By October 25, the Health Department was producing about 7,000 doses of vaccine daily. Two days later, the U.S. Surgeon General was quoted as saying “several vaccines are now being tried. The reports so far received, however, do not permit any conclusion whatsoever regarding the efficacy of these vaccines or their relative merits.” Uncertainty reigned, then as now.

Unconventional and presumptive cures arose then as now. One cure pushed by Dr. George Baer of the “homeopathic hospital” staff in Pittsburgh, Pa., was a hypodermic injection of a solution of 1.54 grams of iodine combined with “creosote and gunicaol,” whatever gunicaol is!

Pandemics produced political conflicts, then and now. In the midst of the 1918 flu peak, Al Smith, candidate for governor of New York, had an upstate campaign stop scheduled in the town of Hornell. When he discovered Hornell was closed to public gatherings, he blamed the Republicans for trying to prevent him from speaking by needlessly closing the town.

Not many social epidemic practices are new (or lacking) in the Covid-19 age. Fortunately, one missing is the caution against public spitting: Back when spittoons were ubiquitous, Spanish flu produced a pushback reported in the New York Times. “The spitting campaign continues without let up. The sanitary police summoned 152 persons into court yesterday, and of these, 124 were fined from $1 to $20.”

The court magistrate is quoted saying, “Beginning tomorrow I am going to hand out a sentence of five days in the workhouse without an option of a fine.” The Spanish flu didn’t stop public spitting, but something later did (almost). Perhaps, as with shaking hands nowadays, Spanish flu was the first strike.

[Harold Brown is Professor Emeritus at the University of Georgia and a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. Established in 1991, the Foundation is a trusted, independent resource for voters and elected officials. The Foundation provides actionable solutions to real-life problems by bringing people together.]

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.