The writer who first caught my interest was John Steinbeck. I will spare you the details of how that happened, but over a two-year period in my early 40s I read everything he wrote and published, and then I studied his life. It was a journey of curiosity, reflection and a little bit of self-discovery.

One of the pieces Steinbeck wrote would take some digging to find these days. He titled it “About Ed Ricketts,” published in 1951. Ed “Doc” Ricketts was a marine biologist on Cannery Row in Monterey, Calif., one of the world’s most scenic seacoasts, where sardines and other fishing boat catches were processed and canned for sale.

At the time when Doc and Steinbeck became best friends and philosophical sparring partners, the canneries had closed and turned into rusting and rotting piles of trash. Steinbeck was still a young, struggling, undiscovered writer. In 1948 when Doc was killed, his truck was hit square-on by a train as he drove toward his favorite place to eat a steak. Perhaps Doc had been distracted by hunger or something he had not figured out in his lab.

While the store owners, clerks, working girls and bums of Cannery Row gathered and wondered to each other how they would get along without Doc since he was the resident wizard when they had a problem, Steinbeck sat on a rise looking out on the Pacific Ocean.

When he finished writing “About Ed Ricketts” three years later, Steinbeck had memorialized many things about the somewhat complicated Doc and, as was his style, the depth of his friendship and his love for Doc was implied, wisps of smoke in between the lines but crystal clear to anyone familiar with how he told a story.

He wrote that, while sitting there on the rise quietly reflecting on losing Doc and how tightly connected they had become, he was afraid that someone would want to “say something.”

I am no John Steinbeck, but I share his sentiment of grieving your own way, quietly, internally, when someone I care about dies. I can do without the ceremonial formalities, the mountain of tasks that serve to consume and distract the family at a time when they need to be busy to get them through the hardest period of their sorrow.

For me, the most faithful thing I can do is … remember.

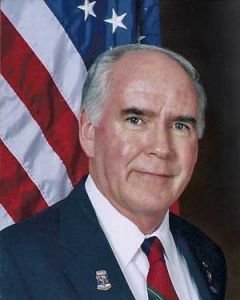

And so it is with Doug Field, who recently passed away, a friend and neighbor. I will tell you a few things about him.

Doug and I were not nearly as close as Steinbeck and Doc, but we did share with each other some of our secrets. There may be more, but I know of three events in Doug’s life he would call miracles.

The first miracle happened on the other side of the world, on Sept. 17 of 1966. Doug was a Rutgers graduate, and he was also a soldier, Army Airborne, a proud member of the 101st Airborne, the Screaming Eagles.

At a place in the jungles of Vietnam known on our maps as Hill 86, near the village of Tuy An, Doug was part of a 15-man unit dug in for the night, part of operation “Nathan Hale” in search of the elusive enemy.

At half past midnight in a downpour, the well-concealed enemy suddenly attacked in an overwhelming force of about 300 men with mortar fire, satchel charges, grenades, .50-caliber machine guns, automatic weapons and eventually after the second wave, hand-to-hand fighting.

Doug’s unit was overrun, and he survived only by successfully playing dead as the enemy kicked bodies and shot the wounded; our enemy was not encumbered by the combat ethics of American soldiers. When the weather cleared the next day and a medevac helicopter was finally able to get in, Doug was one of three wounded survivors flown to hospitals. The other 12 were dead.

Every year as the anniversary of that night approached, Doug was on edge, remembering not just the terror and carnage, but the good men who died too young that night. Good men who live through it carry the burden of survivor’s guilt.

Like Ron Current in Mableton and Alan Walsh in Brooks, medevac pilots and their crew flew multiple missions every day, and because of them many lived who would otherwise have died.

There are thousands of us, including Doug and me, who wish we could find the medevac crew that pulled us out of deep trouble when we were wounded, gave us in-flight emergency care and delivered us to hospitals.

All we want is to look them in the eye and say thanks, especially since they often took breathtaking risks to get to us. But they flew countless missions without detailed record-keeping, so the chances a wounded guy could actually find the Dustoff crew that pulled him out are between slim and none.

Which is where Doug’s second miracle comes in.

At the Peachtree City Post Office in 1998, 32 years after that night on Hill 86, Doug spotted a car with a bumper sticker with the Airborne Eagle insignia of the 101st. He stepped over to introduce himself to Ron Martin, also living in Peachtree City, to commiserate as a fellow Screaming Eagle.

As the conversation took one turn – Ron was a medevac pilot ln Vietnam – and then another, by comparing notes they found that, against a bazillion to one odds, Ron was the medevac pilot that picked up Doug and the two other wounded survivors and flew them to a hospital. A new friendship was formed with a bond that went beyond tight.

The third miracle from Doug’s point of view was his family. As a combat vet with some heavy memories, Doug says he was not always easy to live with and his first marriage failed. I can tell you there is nothing on this planet for which he was more grateful than his marriage to Arline and the family that gave him a second chance. I remember Doug telling me some time ago, with a smile that nearly broke his face, that his son Brian and wife Erin were moving from far away back to Peachtree City.

Arline’s daughter Kellie Hannon, husband Travis and 5-year-old daughter London live in Sandy Springs, which was plenty close enough for Doug to enjoy trying to spoil a grandchild. His eyes lit up when he told me he and Arline were taking London to Disney World, and my grumpiness when I told him how much I despise Disney World deterred him not even one scintilla. He was delighted to have all that time with his grandchild and show her some thrills. Doug’s family was at the pinnacle of his list.

The first thing that will always come to mind when I think about Doug Field is that he was the consummate gentleman. He didn’t have to work at it like I would – ok, even if I tried – because it came naturally to him and he didn’t know how to conduct himself any other way. In other words, Doug could never be me. He was naturally and scrupulously gracious and polite, always properly and carefully dressed, a constant reminder of my own rough edges, though I kept that to myself.

As a soldier and fiercely patriotic American, Doug would have been proud of the men from VFW Post 9949, volunteers who did a nice job as a uniformed honor guard at his funeral, professionally folding the flag and presenting to Doug’s family. Doug would also have been proud of his friend James Barnett, a veteran of the Gulf War, who spontaneously sang the National Anthem a cappella in front of Doug’s casket.

One more thing about Doug Field.

As he knew even better than I know, soldiers in combat don’t fight for the flag, they fight for each other. Even for a guy they don’t particularly like, they will struggle like hell to keep him alive so he can go home, and they have an unspoken mutual pledge: I will remember you.

I didn’t know Doug until recent years, but I will miss him.

And I will remember him.

[Terry Garlock lives in Peachtree City, Ga. He occasionally contributes a column to The Citizen. You can reach him at [email protected].]

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.